|

Jeff Buckley Drowns

By Antony Fine

Daniel Harnett first heard of Jeff Buckley as someone with a cool outgoing

message on his answering machine.

In the fall of 1992 I was playing keyboards in Daniel's band, Glim. We were

gigging at small places–in particular, at  Sin-é, a tiny,

popular folk coffee bar on St. Marks, now closed. We were looking for good

people to share a bill. Daniel recalled: "My friend Rebecca told me about her

friend Jeff and how he'd leave these, like, two-minute-long outgoing messages on

his answering machine that were so elaborate, with lots of voices, and sound

effects–practically little radio plays-and that he’d change them constantly and

I had to check them out. So I'd call just to hear them, even though I didn't

really know him. They were amazing. She also told me he was a good singer. So

just based on that, I invited him to play with us. I knew from those messages he

would be interesting." Sin-é, a tiny,

popular folk coffee bar on St. Marks, now closed. We were looking for good

people to share a bill. Daniel recalled: "My friend Rebecca told me about her

friend Jeff and how he'd leave these, like, two-minute-long outgoing messages on

his answering machine that were so elaborate, with lots of voices, and sound

effects–practically little radio plays-and that he’d change them constantly and

I had to check them out. So I'd call just to hear them, even though I didn't

really know him. They were amazing. She also told me he was a good singer. So

just based on that, I invited him to play with us. I knew from those messages he

would be interesting."

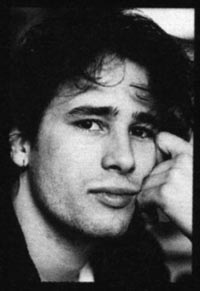

He was. We played with him a lot during that winter and in the spring and

summer of ’93. We were pulling good crowds, and usually Jeff would open for us,

solo. He was an inventive and soulful guitarist, combining gyrating blues licks,

jazz voicings, folk strums, and beautiful, unusual chord progressions, sometimes

within a single line of a song. He was a quirky, engaging performer, talking

directly to the audience members when there were only four or five, stopping

songs in the middle and switching to others when the mood seized him, going

through many moods in a single set. He played a telecaster and a Fender twin

reverb amp, which created a plucking, almost banjo-on-the-porch blues intimacy,

but he also maintained a distance in his gaze. Along with his very pretty

looks-blown-back hair, limpid eyes, sculpted chin and cheekbones-the combination

of exquisite tenderness and strange distance created an aura both erotic and

spiritual, a simultaneous striking in two directions: an opening to the audience

and a pointing away, towards something invisible.

But most striking was what was coming from this face and the darting and

shifting of this enigmatic personality-the voice, a high, slightly reedy sound

the color of burnt honey, arcing and curling like a bird on its long melismatic

wails, reminding one of both a burial song and an orgasm. He sang Billie

Holiday, Van Morrison, Leonard Cohen. He sounded like Robert Plant, Nusrat Fateh

Ali Kahn, Louis Armstrong, Judy Garland. He sounded especially like his

father.

Anyone familiar with Jeff's father said that the physical and vocal

resemblance was striking. Some said even the  mannerisms

were similar. It was especially spooky because Jeff had barely known his father.

His father was Tim Buckley, also a unique singer, songwriter, and guitarist who

released a string of critically acclaimed but commercially unsuccessful albums

during the late 60s and early 70s. He was a genre-crosser, combining folk, jazz,

and psychedelia, and he developed a dedicated cult following before dying of an

overdose of heroin, morphine, and alcohol at 28, in 1975. mannerisms

were similar. It was especially spooky because Jeff had barely known his father.

His father was Tim Buckley, also a unique singer, songwriter, and guitarist who

released a string of critically acclaimed but commercially unsuccessful albums

during the late 60s and early 70s. He was a genre-crosser, combining folk, jazz,

and psychedelia, and he developed a dedicated cult following before dying of an

overdose of heroin, morphine, and alcohol at 28, in 1975.

One Friday night Glim and Jeff caught a train up to a small Hudson river town

just outside of the city to do a benefit show. Afterwards, we crashed at a local

house and sat up until late strumming guitars and singing. The next day I

returned to the city with Jeff, and when the two of us were alone on the subway

we reminisced about New York radio in the 1970's, and sang a lot of those songs.

He could jump into the O’Jays or Stevie Wonder, KC and the Sunshine Band or Joni

Mitchell, with equal ease. We sang "Rollercoaster of Love" together. He was a

wonderful, funny mimic, and had an encyclopedic grasp of all kinds of music. He

once described the lounge composer Esquivel thus: "He’s sort of like if Speedy

Gonzales, as a game show host, had sex with Duke Ellington on acid. That's what

it sounds like."

On that train ride Jeff talked about his father. He said he hadn’t known his

father that well, but he felt him, he remembered him, felt close to him. Jeff

said he disapproved of the way his father had done himself in.But there were

those who felt Tim’s shadow hanging over Jeff so strongly that they seemed to be

waiting for Jeff to self-destruct in the same way. And the higher Jeff climbed,

the more they expected it. He began to climb quickly. Within a few months Jeff

was drawing more people than our little band, and we began opening for him. He

met his future bass player, Mick Grondahl, through one of our shows. He played

steadily at Sin-é. His reputation grew. Our double-billing culminated in a show

at Fez that summer. The detail which I recall most vividly is Jeff holding up

the evening's take in both fists at 3 am, yelling, "Look! Eight hundred dollars!

Eight hundred dollars!", and kissing the bills before generously handing half

over to us. It was the most money any of us had ever made at a show.

Within months he was signed to Columbia Records, a division of Sony, and

released the EP, "Live at Sin-é," which met enough critical success for Sony to

produce his full-length album Grace the following year and support it with a

world tour. Grace was a critical smash, and won Jeff the Rolling Stone award for

Best New Artist, 1995. The album's idiosyncratic blend of musical streams,

including folk, rock, jazz, and Sufi devotional music impressed the American and

European critics enormously. Yet while Jeff's original songs were admired, many

critics seemed most fascinated by Jeff's covers-in particular, "Lilac Wine," a

tender, haunting ballad made famous by Nina Simone, and also Leonard Cohen's

"Hallelujah."

Jeff was rocketed into another world, and although he showed up at our shows

after that, sometimes spontaneously climbing on stage to join us, I saw less of

him. I arrived at Fez once to see him play, only to find the show sold out. He

let me and my friends in for free by sneaking us in the side door. I saw him a

year later at Roseland at the end of his Grace tour, in a gold lamé jacket and

in front of a pit of screaming girls. At the after-concert party at the Batcave,

I sat with some of his other friends gossiping over whom he was talking to in

the back room. Paul McCartney was rumored to be there, to have come to see him.

Jeff had become our transport to the stars, to the big time music business, its

royalty and its courtiers. We never knew for sure where he fit in, but it was

plain he’d been invited aboard. And we wanted to hitch a ride.Yet we, who had

known him in the beginning, felt some weird discomfort seeing him on stage at

Roseland in front of a full rock band, singing through a sound system designed

for arena shows, emphasizing a hollow contemporary vocal-and-drums mix style

inappropriate to his intimacy and exquisite technique. We felt something had

been lost, that he'd perhaps been caught up in something bigger than he could

survive.Jeff had forced many of us to question our categories. He had started

out challenging his audience and himself. Musically he expressed this

questioning by mixing genres and styles, refusing to define himself

stereotypically. Even the question of his sincerity became part of his appeal,

his fascination. Which was the inside, which the outside? Was the star inside

the artist or the artist in the star? Knowing him and trying to figure this out

could become an exercise in endlessly peeling off layers. Jeff became an

embodiment of The Quest. Any good musician recognizes the grail of this quest,

and we all did-the grail of pure connection itself. He seemed close to it. But

at the Roseland show we saw little of that sort of challenging. We saw instead

another rock star in the making. And we worried about him.

In an interview with Rockin’ On magazine in 1995, conducted by Steve Harris,

Jeff was asked about his creative process:

Steve: So I guess your advice to people who want to do the same thing you're

doing is to just keep track of those ideas..

Jeff: and don’t do what I did

and burn your poetry books.

Steve: Why did you burn them?

Jeff: Just

pain...just pain.

Steve: Like, was it a completely hard time, part, of your

life?

Jeff: Well, I have a destructive nature. I have this...Sometimes I

just have this impulse to just destroy things, usually having...to do with

myself.

Months after the Roseland show, I ran into Jeff on the corner of Broadway and

Houston on a hot and crowded Saturday afternoon. He had let his hair grow long

and dyed it black-it was odd-and it looked stringy and he looked a bit pursued.

He lit up when he saw me and as I was saying hello, still recognizing him

through the changed hair, he surprised me with a big bear hug. Then chatted

briefly and separated. My impression was that he was troubled, pursued, worried,

under some cloud.

Daniel Harnett remembered Jeff from about the same time: "I hadn’t seen him

in two years-he’d been on the Grace tour. Now he was back and starting to gather

his new material, and I saw him at a party. I hadn’t seen him in two years, so I

wanted to say, you know, ‘hey, how are you, how’s the music going,’ etc.–you

know, catch up. But Jeff was never conventional in that way. I walked up and

when he saw me, he gave me a big smile, big hug, and–I remember, we were

standing in a courtyard, this was a party in Brooklyn–and before I could ask him

how he was or anything he sort of looked around in the darkness and said, ‘do

you smell, like,...air freshener?’ I sniffed and said, ‘yeah, I do, actually.’

Then he walked away, wandered over to some other group, and I was like,

‘uh...oh, okay.’"

In January of 1996 the Grace tour officially ended, and the word came out

that Jeff was looking for a new drummer. Several friends of mine auditioned,

including Eric Eidel, who wound up rehearsing with Jeff and the band from March

to November 1996. The band practiced four days a week in the same practice space

I was using. I’d often overhear them upstairs jamming, and stop to listen. I

seldom heard Jeff's voice. According to Eric, "He'd bring in songs and we’d work

out arrangements, 1 or 2 co-writing. Sometimes the songs had words, sometimes

they didn’t. It didn’t fall neatly into a style. But there was a conscious

decision not to do any more covers. I think he was growing as a writer,

deliberately focusing more on his own composition."

In June of 1996 the band recorded an EP in New York with Tom Verlaine,

formerly of the band Television, producing. Verlaine had met during sessions for

Patti Smith's "Gone Again." Sony declined to release the EP. Jeff began to

rethink his approach.

"Jeff wanted to go on a solo tour again," said Eric."He had completed songs,

but wanted to return to the process he’d used before, working out the songs’

arrangements in small settings, intimately, letting them take shape through

performance." Eric left the lineup in November 96, and Jeff embarked on a small

solo tour of coffee shops and small bars in the American Midwest, appearing

under assumed names.A new drummer was found in January 97, and the group again

rehearsed a couple of months. It had now been a long time since Grace and the

world was waiting. Jeff booked time at Easley Studios in Memphis, where

Pavement, Sonic Youth, Jon Spencer, Bob Dylan also had recorded. In April 97

they got there and recorded a second EP with Verlaine. There had been rumors of

drug use surrounding Jeff, and the band was reportedly having problems with the

approach Verlaine was pursuing. Jeff and the band decided to record the album in

the summer with Andy Wallace, the producer of Grace, instead of Verlaine. The

band returned to NYC, while Jeff stayed in Memphis alone, continuing to write

and develop material and playing Monday night gigs at Barrister’s, a local

dive.

Daniel said, "Jeff was always looking for the right feel, the right approach.

When they were switching drummers, looking for things to fit just right, it was

like a waiting stage for the right moment for it to all jibe. He’d reached that

point right when he died, according to Michael [Tighe, his guitar player]. He

was living alone in Memphis recording on his 4-track, discovering himself a lot.

He wanted to go with whatever trip it was going to be."

The album was scheduled for May recording, and the band was on its way down

to meet Jeff. On May 29, a friend picked Jeff up on the way to the studio. They

stopped by a marina on the Mississippi, and as the friend sat on the shore

listening to a portable radio, Jeff took a swim, with all his clothes on. The

friend recalls Jeff vanishing for a moment behind the wake of a passing boat,

and then vanishing completely.Eric said: "I think he was impulsive. That sort of

explains why he went into the river and why he was a great musician. He went

with his impulses, which were many and varied. He could be really weird, and

funny, and kind of shamanistic sometimes too. I think he went with impulses, and

he had an intense impulse to go into the water and he went with it."

Daniel said: "He was excited by unpredictable things, and the water is very

unpredictable."In some of Jeff's diary pages his mother had printed for the

program for his memorial service, he wrote: "In order to live my ideal

life...non-evasion and pro-confrontation ORIGINALITY–as far as conducting the

total awareness life in which you plug into "now" and constantly push ahead,

constantly develop and grow. The thing is that I want it all next week, right

now, this millisecond...life should sparkle and rush, burn with fire hot like

melting steel, like freeze-burn from a comet."

Jeff Buckley, singer, songwriter, and guitarist, drowned on May 29, aged 30,

while swimming fully clothed in a marina on the Mississippi River. His body was

found a week later, his death was ruled an accident.

|