Jeff Buckley: The Lost Interview

In this previously unpublished conversation from 1994, captured just days before the release of "Grace", the mythic singer-songwriter pushes through self-doubt, professes his undying love for the Smiths and New York City, and interprets a dream wherein he critiqued a serial killer's photography.

Q: Who and what are you going to become, Jeff?

A: I don't know, just something deeper:

Buckley in 1994. Credit: Michel Linssen/Redferns.

In August of 1994, I interviewed the singer-songwriter Jeff Buckley for over an hour at the New York offices of Columbia Records. Other than pulling a few quotes for a regional music newspaper profile I wrote at the time, this conversation went unused. I put the recording in a box in my closet, where it remained for a quarter-century.

I went back over the transcript a couple of years ago and realized that our conversation offered a rare snapshot of the most pivotal moment in Buckley's too-brief career. He hadn't yet sat for many interviews and was trying to figure out his own narrative, just before he was to leave on a national tour that would make such quiet, thoughtful introspection a luxury.

The son of folk visionary Tim Buckley, he had made his mark in New York City as a solo artist in 1993, performing a suite of original songs and genre-spanning covers with only his guitar and multi-octave vocal range. The buzz didn't really build; it seemed as if one day no one in the city's music scene knew who Jeff Buckley was, and the next, everyone knew.

Prior to entering the studio to record his landmark debut album, Grace, which featured his most successful single, "Last Goodbye," as well as his transcendent rendition of Leonard Cohen's "Hallelujah," Buckley mothballed his troubadour set. To help bring dimension to the music swimming around in his head, he recruited the collaborative working band of guitarist Michael Tighe, bassist Mick Grondahl and drummer Matt Johnson. He wanted his solo album to sound big, ambitious and genre-slippery as he headed to Bearsville Studios in Woodstock, N.Y.

Even though our meeting was less than two weeks before the album release, Buckley was still tinkering with the mixes on Grace, tormenting producer Andy Wallace with sonic flourishes and rewritten bridges, and hoping to squeeze every bit of inspiration out of himself before the tape stopped rolling. In the pre-streaming world, this was an unheard-of high-wire act for a debut artist. But for a young musician who was signed to Columbia Records after a prolonged bidding war, it indicated a bit of acquiescence on the label's part. From what they'd seen of him, Buckley was a can't-miss artist. He just needed time, which, tragically, he was ultimately denied. Jeff Buckley drowned in Memphis in May of 1997, just 30 years old.

I've edited this interview for length and clarity and removed some passages where I thought Buckley's sarcasm could be misinterpreted, or where it spun off into tangents that ended with Buckley impersonating everyone from Paul McCartney to the French poet Baudelaire. He had the nervous energy of someone about to embark on a long journey, uncertain of its destination, and I wanted to ensure his answers would properly reflect not just his wit but his wisdom.

*****

How does it feel to have to do interviews?

Well, at the outset I guess I figured why would anybody care? But I'm smart enough to know that people would want to talk about my music. I just didn't think anyone would for a publication. But at this point the fatigue hasn't set in, and no question is a stupid one.

It's still early.

[laughs] Mainly it's helpful because I'm getting some ideas out about exactly what I think about some things. And the important thing in doing interviews is not to have any pat answers. That would make it unenjoyable for me. Like a … a murder suspect or something, in terms of having your story straight.

Have you finished mixing the new album?

No, I have one last day in the studio — one last gasp of creative breath before I have to go away. I'm totally pissed. Absolutely.

Did you write in the studio, or did you go in with the songs ready?

One of them was completely organized in the studio. But that was still prepared beforehand. A lot of stuff we'd done at the last minute because I was trying to get the right people to play with, and it took a while before I found them.

But that was only three weeks before I'd gone up to Woodstock to record and we hadn't known each other that long, and the band material hadn't developed as much. Some things were completely crystallized, and some things needed care, and they got it. I'm still not satisfied.

Let's see: I get to go into the studio on Wednesday, the day before I leave and the night after I perform at [defunct NYC club] Wetlands. So I have one, two, three, four, five precious days to [work on the music], along with all the other stuff I have to do. I have to shoot some pictures, possibly for the album cover. Then at night I'm free to get these ideas together, and I'll still have one last shot on two songs in particular. The producer [Andy Wallace] doesn't even know what I want to do to this one song. [laughs] He'll be horrified.

Have you played it out?

Uh-huh. There are just things I want to crystallize about it.

Is figuring songs out onstage a conscious effort on your part to fly or fail?

Yeah, because I love flying so much. But, really, it's still a kind of discipline. I guess it's an engagement. It's not like having "song 1 to song 6 and then a talk." I don't know anybody who really does that. I know a lot of performers talk about not being so structured. … Sometimes you can see bands that have a set of songs, and that shit is dead. That … shit … is … dead.

When I perform, I'm working off rhythms that are happening all over the place, real or imagined, and it's interactive. It's got a lot of detail to it, so I can't afford to tie it up in a noose, and put it in a costume that doesn't belong on me. So yeah, it's free but it has its own logic, and sometimes it completely falls flat on its face. But it's worth the fall, sometimes. Because that's life.

To me it makes sense to do things in that manner, because that's really just the way life is when you step out of it and see that, like, your car has a flat and somebody smashed in your windshield and then, shit, you're walking home and all of a sudden you run into somebody that turns out to be your favorite person for the rest of your life. It's always … unfolding. You just have to recognize it, I guess. And that's my philosophy, that I haven't really thought about until you asked me.

Have you been a solo performer out of desire or necessity?

Both. I did it to earn money to pay rent in the place I was staying, and bills, and my horrible CD habit, and failing miserably all the time, always playing for tips and always just getting by — by the skin of my teeth.

To get this sound in order, you can have a path laid out in front of you, but if you don't have the vehicle to go down the road you'll never get to where you want to go. So I guess I was building the parts piece by piece or going through different forms, reforming them and trying out different ideas and songs.

How long have you been building these parts?

Some of them I wrote when I was 18 or 19, and some of them I wrote weeks ago, and some of them I'm still writing. [laughs] The rest of this album is kind of a purging, because the rest of the albums ain't gonna happen like this. [points to chest] You'll never see this person again.

Who and what are you going to become, Jeff?

I don't know, just something deeper. Nothing alien, just something deeper. I'm just not satisfied. I'm really, horribly unsatisfied. Cause I kind of got an idea of where I want this thing to go. It's still gonna be songs. I think about deepening the work that I do, and other problems I try to solve, like, "If I go to see this band in a loft, or if I went to see this band in a theater, and I wanted to be very, very, very enchanted and very engaged and maybe even physically engaged to where I'm dancing or where I'm moshing, what would that sound like? If I wanted to be cradled like a baby or smashed around like a fucking Army sergeant, what would that sound like?" I daydream all the time about it. And that's sort of what I work toward. It's more of an intimate thing.

In America the rock band is not an intimate thing, but in America soul bands are very intimate and blues bands are very intimate, like way back in the day, when people who invented blues were doing it. It's all very interdependent and it's all very … people had to listen to make the music. And it comes around in a lot of different ways. Things I'm doing now are pretty old-fashioned: I'm going on tour to little places to play small cafés. [He lays his itinerary out in front of us.]

What do you expect the reaction to be? You play New York City and, by now, the people here know your deal, but there are some cities where they're not going to know.

That's OK.

Will you tailor your performance to different tour stops? Does it change the way you perform?

Every time I perform it's different.

How long have you been in New York City?

Three years. But I'll always be here. I'll always live here.

What is it about New York?

Everything. You know all the clichés: It's the electricity, it's the creativity, it's the motion. It's the availability of everything at any moment, which creates a complete, innate logic to the place. It's like, there's no reason why I shouldn't have this now. There's no reason I shouldn't have the best library in the country, and there's no reason why the finest Qawwali singer in all of Pakistan shouldn't come to my neighborhood and I'll go see him, and there's no reason that Bob Dylan shouldn't show up at the Supper Club.

There's no reason that I can't do this fucking amazing shit. And if you have a certain amount of self-esteem, it's the perfect place because there's so much. It's majestic and it's the cesspool of America. And there's amazing poetry in everything. There are amazing poets everywhere, and some real horrible mediocrity, and an equal amount of pageantry. There's also a community of people that have been left with nothing but their ability to put on a show, no matter what it is — whether it's a novel or a performance reading on Monday night at St. Mark's Church for 20 minutes.

Where do you do the bulk of your writing?

Everywhere. You know what? Mostly it's in 24-hour diners, on too much coffee. That's an old Los Angeles thing.

How much does the location affect the writing?

To me music is about time and place and the way that it affects you. There's just something about it. There's just some spirit that somebody conjures up and then it floats out at you and helps you or hinders you throughout your life. It's either Handel's Messiah or it's "All Out of Love" by Air Supply.

Music is just fucking insane. It's everything. Music is like this: It's always seemed to me to be one of the direct descendants of the thing in the universe that's making everything work. It's like the direct child of … life, [of] what being "people" is all about. It's incredibly human but it touches things that are around us anyway. [pauses, then quietly] It's hard to explain.

Give it a shot.

It gets into your blood. It could be [the Ohio Express'] "Yummy Yummy Yummy" or whatever. It gets in. It's not like paintings and it's not like sculptures, although those are really amazing and powerful. But I identify with music most.

And is live music the next degree of intensity?

Oh yeah, if they're singing to me. You never hear it again, but you never forget it. I mean, you never forget it. It's like the first time your mother cries in front of you. But I like making [music] and … I want the music to live live, even be written live, so it's always forming, it's ever unfolding.

The king of improvisation is [the late Qawwali singer] Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan — the most I've ever been filled with any performer's energy. I have over $500 of his stuff. And I never got to see Keith Jarrett, but there was a time when he was my big hero for the same reason. Big, huge improvisation. Improvisation is something that I identify with.

Which of your new songs is your favorite? Is there one that you can't wait to get to in your live set?

Not yet. I give each song pretty much the same attention, and I have the same reservations and the same carefulness about making sure I bring out its best. No favorites.

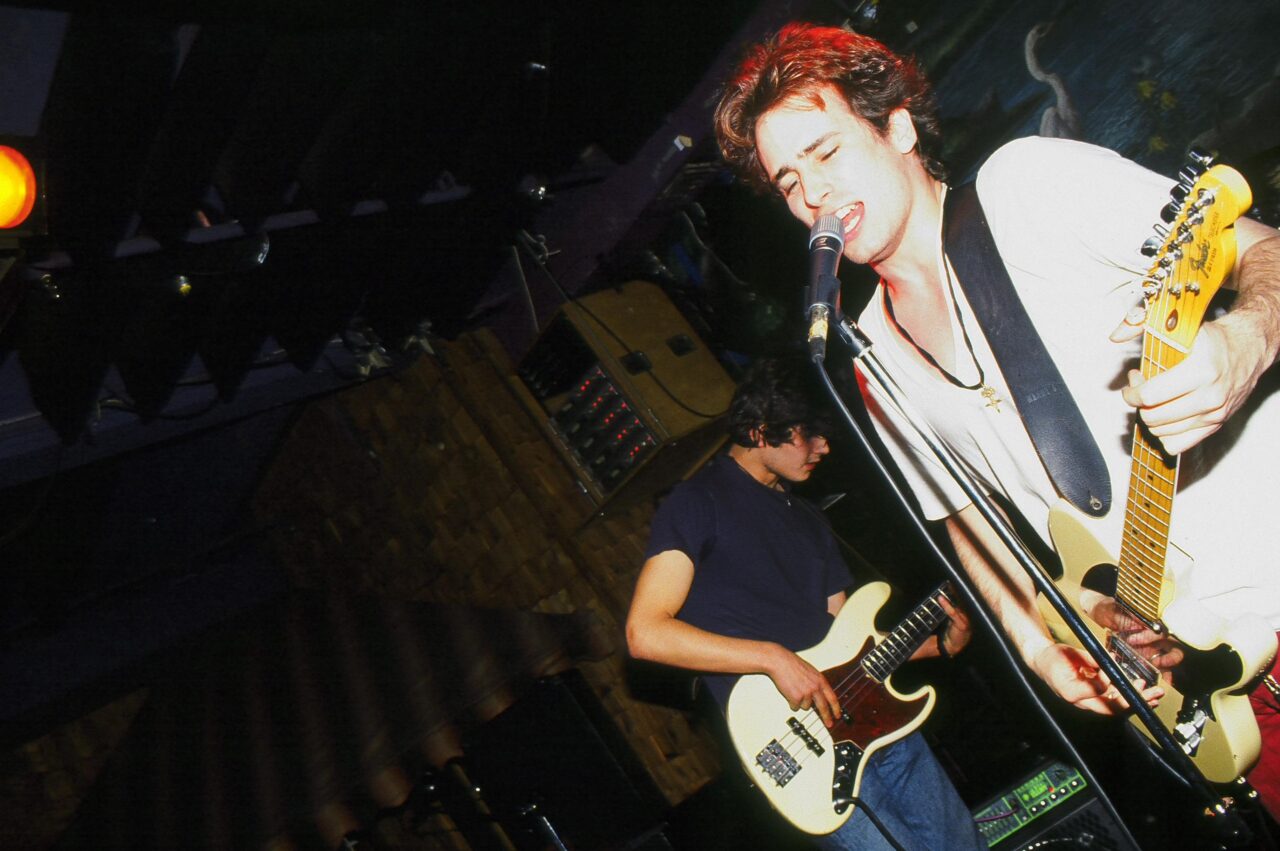

Just days after this conversation, Buckley gigs at the storied NYC club Wetlands. This performance was immortalized in a posthumous live release.

Credit: Steve Eichner/Getty Images.

What's a song by another artist that you wish you'd written, that completely devastates you?

Most of Nina Simone's songs completely devastate me, although she didn't write [most of] them. A lot of things that Dylan did are so impressionistic, even though his originals are supposed to be folky. Like "Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands": If I was a woman and he sang that to me, I'd be like, "Whatever you want, Bob. You want casual sex whenever you want it and still be with your wife? I don't care."

I'd like to write something like "Moanin' for My Baby" by Howlin' Wolf, and I'd also like to write something like [Gerry and the Pacemakers'] "You'll Never Walk Alone." I have schoolgirl crushes on a lot of songs that never seem to go away. Lots of Cocteau Twins. That's somebody I got to tell exactly what I thought of them.

Where were they playing?

In Los Angeles, a long time ago on the Heaven or Las Vegas tour. I'm immensely in love with their originality, their shyness. … But … um … the Smiths! [stands up abruptly, then sits back down] I wish I'd written half the fucking Smiths catalog. There are so many: "I Know It's Over"; I wish I'd written "How Soon Is Now?" I wish I'd written "Holidays in the Sun" by the Sex Pistols. I could go on forever, and I know you don't have forever.

Maybe sleep on it. I'm curious, do you sleep a lot?

No, I don't.

Is your mind constantly racing? Are you always just … fast forward?

Have you ever seen those film montages when a guy's going crazy, and it just gets faster and faster and…

Yeah, sure, that's exactly what I mean.

It's exactly like that. It's like, I don't want to miss a thing, and [I get the] feeling that I will miss something. But usually I'm wrong. [laughs] But when I do sleep, I sleep hard and have the best dreams.

Do you remember your dreams?

Sometimes, and they become the basis for a lot of my learning. That comes along with my development as a human being. Lately I've been having a lot of killer dreams — like a killer is coming after me or I have to confront a killer. And when a killer is coming after me, what am I going to have to do? To kill him.

Interesting. What do you think that means?

That something in me is going to be murdered. That a psychic killer is coming. Actually, I met him. Sometimes I meet people inside of me that don't like me; sometimes I meet people inside of me that want to make love with me more than anything; sometimes I meet the most bizarre animals and am in the most bizarre situations.

One dream, I met a serial killer who lived out in a small town in, like, Virginia. A small suburban town, very nice, white picket fence. And he lived in the town in a church with the pews taken out. And he was an artist.

You remember this much detail?

Just wait. He was a very short young man, probably about 28 years old with thinning black hair that I think he was ashamed of. He also had all of these photos of these people mangled beyond belief, carved up, dissected alive. They were still alive in these photos, and there was a wall of all of these seductively beautiful, textured, processed black-and-white photos. One man had been made into a basket. One man had been totally deboned but still kept alive, and his skin had been made into a basket upon which his head stood, looking straight into the camera. And right before he died, this snapshot was taken. And this is what this guy's job was. And my task in the dream, I was the person that saw this amazing horror and this amazing pain. The photographs were screaming, and all of this madness, all of this waste at the hands of this person with a warped soul.

The irony of the dream was that his self-esteem was nothing, and he was saying, "This sucks. This is horrible. I don't even want to show you." I was so afraid of him and wanted to keep him in the same place long enough for the police to get him and take him away — while not being killed myself. Obviously. [laughs] So in order to be cool I had to ultimately be compassionate and point out the details in the picture where I felt there was brilliance and really good workmanship — all the while feeling that I would vomit any second, all the while so scared I thought I would cry. And that was the dream.

Sometimes I have really rhapsodic dreams, and sometimes I have little bits of memory … but lately it's been killer dreams, and the police almost don't come in time, although they do come in time. And then I met a woman inside me that hates me. I met the girl, I met the person that doesn't like me, and then I met this person who was so lascivious sexually that she masturbates publicly all of the time, like she's fixing her hair. And she looks beautiful doing it and really great, but everyone's around her and she's practically naked.

I'm pretty transfixed by [dreams]. I link them to the way I perform. I don't see any separation, because when you sing there's a psychic journey that happens.

Do you write a lot of poetry?

I garner my songs from my poetry.If anything looks like it's vibrating, yeah. But it's a raw thing.

Was the Live at Sin-é EP, released in November of '93, supposed to hold people over until the album comes out?

No, it served that purpose, but no, it's just because I love that place.

How often have you played there?

I've played there a lot. I played there for over a year. At first I couldn't get a slot. Shane [Doyle], the owner, had too many demos to listen to. I gave him a demo and a review, which is something I never ever, ever fucking do: pay credence to any one journalist's opinion. But this was a good review. [laughs] Some positive, some negative. Mainly the negative stuff was my fault.

So I thought that maybe I could get a gig at this little place because I wanted to play in little places to establish my sound and do the work and learn how to sing the way I wanted to sing. Because I didn't have any teachers. There were teachers around Sin-é to teach what I needed to learn, but Shane couldn't be bothered.

Then somebody crapped out on a bunch of Monday nights and my friend Daniel Harnett got me in. He said, "I'm doing one, and so you can do one too." I was like, "Wow, thank you." As it turned out, that was it. Bang! I really worked my ass off to get that gig and get others and to make money.

How did you hook up with Columbia Records?

They came to me. I didn't intend for them to. I was just making music.

Were they the only label that came to you?

Nope. I met Clive Davis. Shook his hand. I met Seymour Stein. Seymour's at Sire; Clive is at Arista. A lot of people were interested. I met somebody from RCA. Peter Koepke at London.

Were they in the audience at your shows? Then they'd come up to you afterward?

Yeah, and I didn't really like it. I didn't like Clive showing up in a limousine on the Lower East Side, in a fine suit. Poor guy — it was so hot in that fucking room.

This was Sin-é, right?

Yep, you were there — like a fucking furnace. In the middle of the fucking summer. I had my shirt off; the guy's still in his work clothes 'cause his life is fully air-conditioned.

Did you have any misgivings about signing?

Of course I did. Being brought up around the music business in Los Angeles, you see the turnover of people being signed and dropped day after day after day, and it's all written off as a tax loss. To the company, it's no sweat off their nose.

But here in New York it's more about the work, and you don't get anywhere without the work and that's what I was doing. But I had misgivings about the size of the places. I had misgivings about my deservedness, about how good I was. I had misgivings about who they thought I was and what they thought I was. And how I wasn't what they thought. At all.

Which is? Don't record companies think that every male solo performer with a guitar is the New Dylan?

No, they thought I was the second coming of Tim Buckley. [quietly] That's what I thought they thought.

Is that a recurring worry of yours?

It was that as a child. But now I'm totally immersed in what I do. If someone asks a question about it, I just tell them as much truth about things as I know. I had no misgivings once I saw my first and only liaison to Columbia Records, [former head of A&R] Steve Berkowitz. He was there from a pretty early stage, just listening. Which is what he does. Because he loves music. And he's smart. And he's smart enough to work this fucking gig at Columbia and to do a good job. The personnel here [at Columbia] are what really changed my worries, but I'm really worried up until, like, now.

How would you describe your sound?

I can't explain it because I'm actually confused. It's not really a tremendous literary feat to describe it. It's just an amalgam of everything I've ever loved and everything that's ever inspired me. I'm using that now.

How do the Columbia folks describe you?

They don't know. At a recent convention I played in Boca Raton for A&R folks at like 11 in the morning, the guy that introduced me said, "We really don't know what this is. We don't know what kind of record he's gonna make. We just know he has to make it."

... a.k.a. "Introducing the boy genius..."

I'm not a boy genius. I'm neither one, actually. But I'm aware that these people have to move units. I'm aware that this company, by inertia alone, has an agenda. That it can function without me, and I can function without it. But there's a certain thing that I can't have without it, and that's making little plastic discs and traveling the world and being a musician, and they seem to want me. A lot. And I feel that where I'm going is worthwhile, that maybe when I get there this all will have been … whatever crappy shit I've ever done will be redeemed.

Do you think you'll ever get there?

Sure. Or you'll find me swinging from somebody's dressing room [laughs] with a big blue arm holding a Jam tape.

Source: Tony Gervino - July 21, 2022

|